Artikkelit

01.10.2025

Education at a Glance — Barely a Glance at China

The Education at a Glance 2025 report includes China as a “partner economy,” but offers little narrative or detailed analysis specific to the country. Much of the data on China is outdated or incomplete, reflecting broader challenges with data transparency and non-member participation in OECD frameworks. While China's educational attainment—particularly in higher education—is clearly growing, its limited visibility in international reports highlights the difficulty of integrating China into global education comparisons and discourse.

In the Education at a Glance 2025 report, China is listed as one of the so-called “partner economies” in the country coverage, meaning it is included among non-OECD members whose data are used in comparative tables. However, very few China-specific findings are highlighted in the report itself. Most notably, no separate “country note” for China—similar to those provided for Germany, Japan, or many others—has been published. In other words, the report lacks a dedicated narrative or analysis focusing on China’s recent educational performance. This is not unique to China. OECD “country notes” or thematic profiles typically exist only for member countries; partner economies, including China, usually appear only in statistical tables, without accompanying analysis. Apart from some technical contributions, the list of contributors to the report does not appear to include any Chinese authors.

Moreover, much of the data cited for China is outdated, making meaningful comparisons difficult and, at times, potentially misleading. This is likely due to China’s non-OECD member status. For example, data from UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics are sometimes used in place of figures collected directly through the OECD’s own systems. Of course, this is also not a China-specific issue—OECD’s methodology prioritizes data from member states, and partner economies often provide figures via alternative or indirect channels. Most importantly, significant data gaps remain. For example, information on China’s educational spending is limited; no detailed data are available on the percentage of young adults in China with tertiary education, and very little is published about student–teacher ratios or class sizes.

Even with partial data, however, it can be inferred that China has made considerable progress in educational attainment, at least up to the years for which data are available. While detailed numbers are scarce, available information suggests that China’s tertiary attainment is growing—perhaps nearing or even surpassing that of many partner economies. This aligns with both scholarly assessments and claims made by Chinese government sources. For example, official statistics indicate that the country’s gross higher education enrollment rate has now exceeded 60%. Unsurprisingly, given China’s large population, the absolute number of students and tertiary graduates is among the highest in the world. Financial data suggest that education spending is tracked to some extent, but many key indicators remain unpublished. This reflects broader patterns in China’s approach to data transparency, and makes it difficult to assess the country’s precise trajectory in international educational comparisons.

No major Chinese media channel has reported on the findings of the 2025 report. Historically, political and public discussions around these reports in China have tended to come from educational policy research institutions, university-affiliated platforms, or specialized education media, rather than government outlets. For example, last year, a research body affiliated with Shanghai Normal University published a brief news item on the 2024 report, titled: “OECD Releases Education at a Glance 2024 Focusing on Education Equity” (“经合组织发布《2024年教育概览》聚焦教育公平”). As this example indicates, the reports are not fully translated into Chinese; at best, summaries of key findings are selectively published. Common themes in these publications include education equity, comparisons with OECD averages, access to higher education, gender balance, and disparities between urban and rural areas or across provinces.

Like many international reports in education and other sectors, Education at a Glance tends to be largely ignored by the broader Chinese public. The Chinese media tend to prioritize domestic policy pronouncements or nationally framed reforms over external comparative reports, but one might expect at least some coverage—particularly given that domestic media does at times highlight international rankings or comparisons that frame China’s achievements positively. Part of this limited attention may be due to the report’s recent release. In China, reporting on such topics often takes time, possibly because news and analysis go through multiple layers of official screening and review before publication.

Nevertheless, while the report has not received significant coverage on Chinese social media platforms compared to Western countries, it still surfaces occasionally on forums such as Zhihu, Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), and Weibo. As with more traditional media, discussions on these platforms typically revolve around issues of educational fairness and international comparisons—and occasionally adopt a critical tone, despite the limitations imposed by censorship.

In sum, while educational development in China is clearly advancing in line with national strategies such as the Ministry of Education’s “Blueprint for Building a Strong Education Country by 2035,” the absence of reliable, disaggregated data and the limited public discourse surrounding the Education at a Glance report underscore how difficult it remains to fully integrate China into global educational dialogue and evidence-based comparison.

Text: Olli Suominen

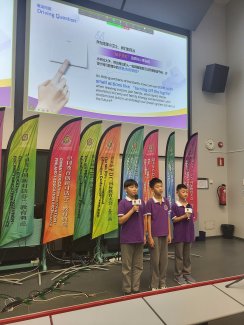

Photo: Chinese pupils attending a Finland-China educational event at the University of Helsinki. Credits: Olli Suominen